Stacey Fitzsimmons, University of Victoria; Jen Baggs, University of Victoria, and Mary Yoko Brannen, University of Victoria

Conventional wisdom suggests that first-generation immigrants often struggle in their careers for reasons related to being new to the domestic workforce.

For example, offshore degrees, poor language fluency or an absence of networking contacts are cited as common reasons for career challenges. This means most efforts to improve immigrants’ career outcomes often focus on things first-generation immigrants can do for themselves, like networking and training.

We wanted to know whether this is actually the best approach. Our evidence about which groups get paid the most versus which earn the least points to an alternative that may be even more effective: reducing workplace discrimination based on gender and race.

Who earns the most and the least?

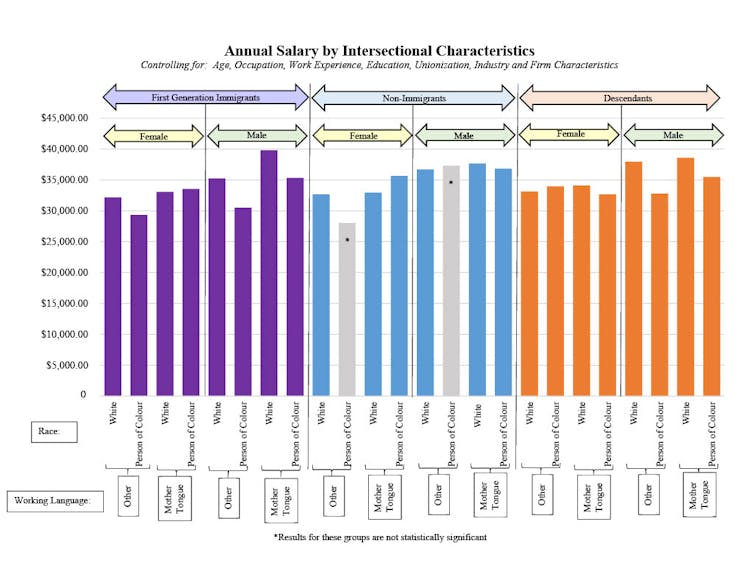

To find out why immigrants receive lower pay, we looked at who earns more or less as a result of their combination of immigrant generation, gender, race and native language. We also wanted to find out whether being a first-generation immigrant is really the most important factor in terms of salary. (Spoiler alert: it’s not, according to our findings.)

We compared the annual pay for a sample of 20,000 employees within 6,000 firms that represent Canada’s workforce. Canada is a particularly good test case for examining immigrants’ outcomes because of its high proportion of first- or second-generation immigrants (37.5 per cent of the population).

We took an “intersectional” approach to this research. That means we looked at all 24 possible combinations of these four characteristics, rather than measuring how much each characteristic impacts pay on its own:

· Immigrant generation: First-generation, referring to those born abroad; descendants, referring to their Canadian-born children and grandchildren; and non-immigrants, referring to those who are not recently descended from immigrants

· Gender: Men and women

· Race: Self-identified as a person of colour, or not

· Language: Whether the person works in their native language or in an additional language.

Big-picture comparisons

We recognize that these are all rough categories that ignore important complexities. For example, because of data limitations, we couldn’t test for different outcomes between racial groups or across the full gender spectrum.

Despite this lack of nuance, rough categories can still be useful as a starting point for making big-picture comparisons between groups.

Finally, we compared “apples-to-apples” by controlling for five individual characteristics (age, experience, education, occupation and unionization) plus four characteristics of their workplaces (size, industry, performance and international competition). That means we aren’t comparing entrepreneurial housekeepers in one group against corporate data analysts in another.

Authors’ calculations, Author provided

First-generation immigrant white men — most of them from the U.K., France or the United States — working in their native language have the highest pay of any group, including non-immigrants, and are closely followed by their sons.

In contrast, another group of first-generation immigrants — racialized women who are neither anglophone nor francophone — earn the least. The gap in annual income between these two groups of first-generation immigrants, even after controlling for other explanations like education and experience, is close to $10,000.

This shows why it doesn’t make sense to talk about first-generation immigrants in the workplace as though most of them share similar experiences.

It is possible to see the combined effect of race and gender for first-generation immigrants who all work in their mother tongues. White men received $6,263 more in annual pay than women of colour. These results emphasize the importance of looking at multiple characteristics together when considering the employment experiences of immigrants.

What to do about it?

Investing in diversity and inclusion more generally is one step that may help the immigrant employees who need it most. However, a more effective approach may be to directly target those groups most disadvantaged; for example, focusing on immigrant women of colour, rather than broad diversity initiatives.

Immigrants, women and people of colour have very different employment experiences, and these differences are even bigger when considering these characteristics in combination.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

Businesses that recognize these differences will be better placed to reduce unfair pay gaps and capture the full value of a diverse workforce. A recent report suggests the onus is on employers to actively recruit newcomers through immigrant services organizations like Vancouver’s MOSAIC, Toronto’s ACCESS Employment and Montréal’s le Collectif.

Ultimately, our findings suggest that no matter how much education, training or networking that racialized female immigrants do, they are still earning less than their peers. That means it’s up to employers to remove employment barriers and recognize the benefits of all their employees.![]()

Stacey Fitzsimmons, Associate Professor of International Business, University of Victoria; Jen Baggs, Associate Professor, Economics, University of Victoria, and Mary Yoko Brannen, Honorary Professor of International Business, Copenhagen Business School Professor Emerita San Jose State University, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured Image: Intake workers assist visitors at an immigrant and refugee vaccine clinic set up by Global Medic in Toronto in April. Research suggests racialized immigrant women earn less money than other groups, regardless of how much training, education or networking they do.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn