Ahmad Al-Rubaye/AFP via Getty Images

Michael Fakhri, University of Oregon and Ntina Tzouvala, Australian National University

According to a new United Nations report, global rates of hunger and malnutrition are on the rise. The report estimates that in 2019, 690 million people – 8.9% of the world’s population – were undernourished. It predicts that this number will exceed 840 million by 2030.

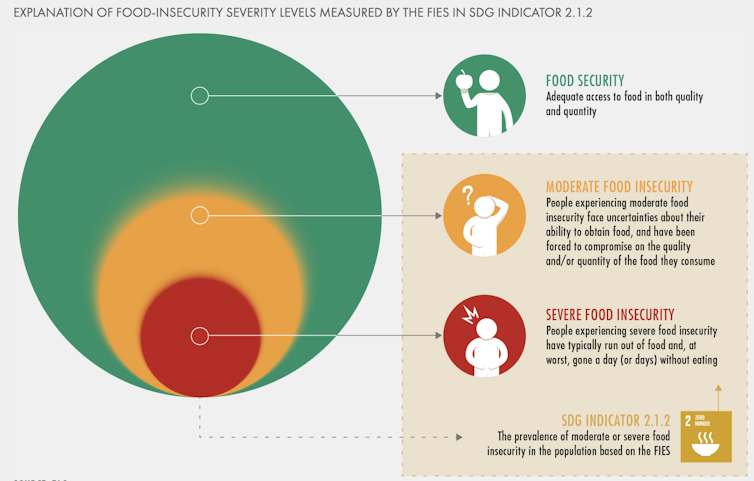

If you also include the number of people who the U.N. describes as food insecure, meaning that they have trouble getting access to food, over 2 billion people worldwide are in trouble. This includes people in wealthy, middle-income and low-income countries.

The report further confirms that women are more likely to face moderate to severe food insecurity than men, and that little progress has been achieved on this front in the past several years. Overall, its findings warn that eradicating hunger by 2030 – one of the U.N.‘s main Sustainable Development Goals – looks increasingly unlikely.

COVID-19 has only made matters worse: The report estimates that the unfolding pandemic and its accompanying economic recession will push an additional 83 million to 132 million people into undernourishment. But based on our work serving as independent experts to the U.N. on hunger, access to food and malnutrition, under the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, it’s clear to us that the virus is only accelerating existing trends. It is not driving the rising numbers of hungry and food-insecure people.

FAO, CC BY-ND

How much should healthy food cost?

Experts have debated for years how best to measure hunger and malnutrition. In the past, the U.N. focused almost exclusively on calories – an approach that researchers and advocacy groups criticized as too narrow.

This year’s report takes a more thoughtful approach that focuses on access to healthy diets. One thing it found is that when governments primarily focused on making sure people had enough calories, they did so by supporting large transnational corporations and by making fatty, sweet and highly-processed foods cheap and accessible.

This perspective raises some important issues about the global political economy of food. As the new report points out, people who live at the current global poverty level of US$1.90 per day cannot feasibly secure access to a healthy diet, even under the most optimistic scenarios.

More broadly, the U.N. report addresses one of the longest-running debates in agriculture: What is a fair price for healthy food?

One thing everyone agrees on is that a plant-heavy diet is best for human health and the planet. But if prices for fruits and vegetables are too low, then farmers can’t make a living, and will grow something more lucrative or quit farming altogether. And costs eventually go up for consumers as the supply dwindles. Conversely, if the price is too high, then most people can’t afford healthy food and will resort to eating whatever they can afford – often, cheap processed foods.

The role of governments

Food prices don’t just reflect supply and demand. As the report notes, government policies always directly or indirectly influence them.

Some countries raise taxes at the border, making imported food more expensive in order to protect local producers and ensure a stable supply of food. Rich countries like the U.S., Canada, and in the EU heavily subsidize their farming sectors.

Governments can also spend public money on programs like farmer education or school meals, or invest in better roads and storage facilities. Another option is to grant people living in poverty food vouchers or cash to buy food, or to ensure everyone has a basic income that allows them to cover their fundamental spending. There’s a host of ways in which governments can make sure food prices allow producers to make a living and consumers to afford healthy meals.

The human cost of cheap food

The U.N. report focuses on trying to make sure that food is as cheap as possible. This is limited in a number of ways.

New research highlights that mostly focusing on cheap prices can promote environmental damage and brutal economic systems. That’s because only large corporations can afford to compete in a market committed to cheap food. As our research has shown, today and in the past, people’s access to food is usually determined by how much power is concentrated in the hands of the few.

One current example is meatpacking plants, which have been coronavirus transmission centers in the U.S., Canada, Brazil and Europe. To keep prices low, people work shoulder-to-shoulder processing meat at an incredible speed. During the pandemic, these conditions have enabled the virus to spread among workers, and outbreaks in factories have then spread the virus to nearby communities.

New international standards allow factories to continue to operate, but in a way that protects workers. In our view, governments are not adequately enforcing these safety standards to stop the spread of the virus. Globally, four corporations – Brazil’s JBS, Tyson and Cargill in the United States, and Chinese-owned Smithfield Foods – dominate the meat-producing sector. Studies have shown that they are able to lobby and influence government policy in ways that prioritize profit over worker and community safety.

Our work has convinced us that the best way for governments to make sure that everyone has access to good food is to view a healthy diet as a human right. This means first understanding who has the most power over food supplies. Ultimately, it means making sure that the health, safety and dignity of people who produce the world’s food is a central part of the conversation about the cost of healthy diets.

This article was updated to correct the figure for predicted undernourishment.![]()

Michael Fakhri, Associate Professor of International Law, University of Oregon and Ntina Tzouvala, Senior Lecturer in International Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.